A Good Problem to Have

This post describes a novel way to use probabilistic data structures to improve the user experience of creating a new account.

You run a site where customers create an account with a user name and password. Your site is wildly successful and more customers flock to join. Soon all the good user names are taken. With all your success the fundamental user experience of creating an account begins to suck.

Why? The first group of users naturally choose their first name. But there are 4.8 million James in the United States and almost as many Johns. The twenty most common male names account for 32 percent of the male population. There are about 4 million Marys and 1.6 million Patricias. Incredibly prospective customers are told, “Sorry, username ‘Maurice’ is already taken”.

First initial and last name will go a lot further. However, thanks to human psychology, we again run out of steam sooner than you expect. At my company, there were three John Lloyds. Some first names just sound better with a last name like John and Lloyd. As a parent of five I can attest to thinking a lot about that.

Username validation requirements

By the time you reach 50,000 users (congratulations, by the way) your sucky UI will require the user to make repeated attempts to find a name that is not taken. Some frustrated non-customers are giving up; now you need to fix this problem quickly. For the ideal user experience your account creation UI needs to be simple and responsive. It should have these properties:

- A visual queue that the name being typed is not yet taken

- Less than 0.5s latency when checking if a given name is taken

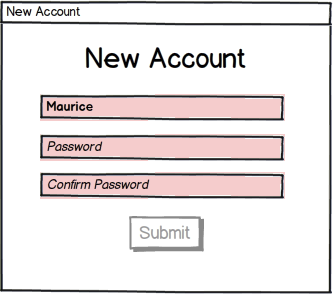

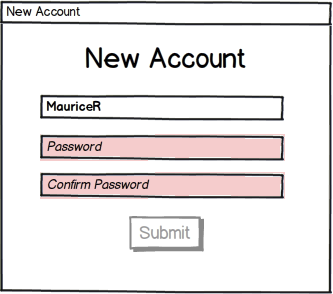

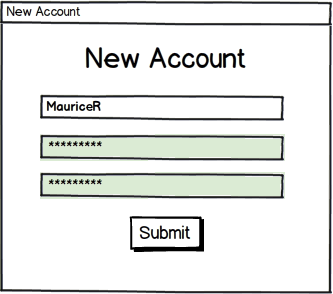

The visual queue could be a greyed out “Submit” button whenever the name is already taken. It could also be a pink background in the user name text input box. With these improvements, your customers will once again be able to choose a name easily without the heartbreak of repeated rejections. The low latency is needed for the impression of a responsive UI.

|

|

|

The three images above show how a simple dialog can provide feedback for a taken username, a weak password, and a non-matching confirmation. In all cases the background is pink when there is a problem. The submit button is enabled only once all three problems are eliminated. Doing all three checks on the client side leads to a responsive and simple user experience.

Probabilistic data structures

This type of behavior should be done in JavaScript on the browser. Unfortunately, you can’t just download a long list of taken names. Even a trie of names is too big. A trie can compress common prefixes but the number of nodes is still proportional to the number of distinct names in the trie. The sheer number of names appears to make a client side solution impossible. Unless of course you are willing to trade off certainty for size.

Enter a probabilistic data structure called a Bloom Filter. Probabilistic algorithms behave like normal algorithms but have a theoretical chance of being wrong. The trade off is that they act faster or require less memory to produce the result.

A Bloom Filter is a probabilistic (unreliable) set. Unlike a trie, a Bloom Filter can compress both the letters and the number of words in a collection to an in-memory bit vector. You can’t always trust that a true result from testing set membership is correct, but a simple formula gives statistical limits on the number of false positives. Here is how it works.

Suppose the bit vector has size M, where M is very large. To add user name S to the filter, compute k hash values ${h_0(S), h_1(S), …, h_k(S)}$ and set those bits to 1. The k hash functions should be independent. The numbers M and k are selected based on the expected number of names. Checking for the presence of a name involves calculating the same set of bits and testing it they are set. If even one of them is not set, then the name could not be present in the filter. If, however, they are all set, the name is only likely to be present.

The space advantage in a Bloom Filter comes from the compactness from the data structure. A Bloom filter with 1% error and an optimal value of k, requires only about 9.6 bits (1.2 bytes) per element — regardless of the size of the elements. So a site with 50,000 user names would require 64K bytes for a filter. That’s the size of a small (400x600) gif image.

A word of caution. The theoretical percent error assumes the hash functions are mutually independent. It is not that easy to get a family of independent hash functions, but based on my research the error is not too far off.

Edge cases and Recommendations

There is a delay between the time that the bloom filter is calculated on the server and when it is used on the client. Suppose for the sake of argument that your site has 50,000 names and adds 600 more users every day. The bloom filter may be recalculated 6 times a day and republished.

If a new user happens to pick one if these 100 new user names before they are added they might still get a false negative.

What do you do when a false negative happens? The simplest solution is to blame latency. The user does not know that we are calculating taken names locally using a Bloom Filter. The UI could optimistically send the names being typed (after a 0.5 second pause) on to the server to validate. If the latency to your server is small, the additional check will only take an extra second. If the name is indeed still not taken, the “Submit” button can be enabled. If it happened to be among the 100 newly added names, that fact is sent to the client which adds the name to a stop-list of known taken names. The stop-list can be uploaded along with the Bloom Filter.

As you start out your web site all you really need is a stop-list to get the same user experience. One thousand 20 letter user names is only 20K un-compressed. Design your UX to scale up to 50 or 100 times as many users and change the test to use a bloom filter when the download size of the stop-list gets too big.

Limitations and Conclusion

Facebook has over 1.8 billion active users. A Bloom Filter solution will not scale to Facebook proportions. Google has the same ‘problem’. In these cases validation happens on the server and the server suggests a number of unused names to the user following certain patterns. Can you think of a way in which the giant could improve on this?

Good luck and I hope you enjoyed my first technical blog post. In the future I will share some code for making fast username validation happen.